Saturday November 19, 1904

To understand Doris, you have to understand the circumstances of her birth; so please imagine, if you will, that that is today’s date. Today is the day that Boston banker and broker S. Reed Anthony signed a contract at the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company in Bristol, Rhode Island to have what is considered a medium-sized cruising sloop built. Likely no one realized that this would be the largest all-wood sailing yacht ever built at Herreshoff, as her particulars were inked into line #625 of the red-leather-bound, tan corduroy Construction Record; and while we don’t yet know the namesake, the name recorded was “D-o-r-i-s”.

The Gilded Age

One thing you must understand to put this in context is that today, the rich are very, very rich. 110 years from now, in 2014, Americans will believe that there is shocking income disparity between the upper and lower classes – but it will be nothing compared to here around the turn of the 20th century. The wealthiest people in modern history are alive. The richest American ever, John D. Rockefeller is retired now, but still added sixty million dollars to his personal fortune of over $200 million last year (equivalent to a net worth of around $130 – $200 billion in 2014). But, this unchecked power of the wealthy has shown it’s first cracks recently. This year, a woman named Ida Tarbell wrote a book called The History of the Standard Oil Company, which told about the ruthlessness that allowed Rockefeller to accrue such wealth. The President of the United States was a good friend to the powerful until three years ago when he was shot and killed, but his Vice President who took over came out as an anti-monopolist, and just eleven days ago he was elected to his first term in his own right: In 1899, President McKinley ordered U.S. Navy torpedo boats to keep the course clear as the Herreshoff sloop Columbia defended the America’s Cup; in 1902, President Roosevelt filed the first anti-trust lawsuit brought by the federal government under the Sherman Antitrust Act against the Northern Securities Co., a railroad trust that included Columbia’s principal owner J.P. Morgan and J.D. Rockefeller. On March 14th of this year, the Supreme Court decided against Northern Securities, and the company was broken up. So, times are changing, and the wealthy soon won’t be quite as wealthy as they are now – but in 1904 we don’t know that yet.

One thing you must understand to put this in context is that today, the rich are very, very rich. 110 years from now, in 2014, Americans will believe that there is shocking income disparity between the upper and lower classes – but it will be nothing compared to here around the turn of the 20th century. The wealthiest people in modern history are alive. The richest American ever, John D. Rockefeller is retired now, but still added sixty million dollars to his personal fortune of over $200 million last year (equivalent to a net worth of around $130 – $200 billion in 2014). But, this unchecked power of the wealthy has shown it’s first cracks recently. This year, a woman named Ida Tarbell wrote a book called The History of the Standard Oil Company, which told about the ruthlessness that allowed Rockefeller to accrue such wealth. The President of the United States was a good friend to the powerful until three years ago when he was shot and killed, but his Vice President who took over came out as an anti-monopolist, and just eleven days ago he was elected to his first term in his own right: In 1899, President McKinley ordered U.S. Navy torpedo boats to keep the course clear as the Herreshoff sloop Columbia defended the America’s Cup; in 1902, President Roosevelt filed the first anti-trust lawsuit brought by the federal government under the Sherman Antitrust Act against the Northern Securities Co., a railroad trust that included Columbia’s principal owner J.P. Morgan and J.D. Rockefeller. On March 14th of this year, the Supreme Court decided against Northern Securities, and the company was broken up. So, times are changing, and the wealthy soon won’t be quite as wealthy as they are now – but in 1904 we don’t know that yet.

You often hear the wealthy say “It’s not about the money, it’s about winning.” A millionaire in 1904 would have been hard-pressed to spend such a fortune in a lifetime, yet they were often at war with each other, and a by-product of “winning” was amassing more fortune. But their competition extended to spending money as well: if one of the Captains of Industry gained notoriety for an art collection, or a botanical garden, or a racehorse stables, or a racing yacht – you can rest assured that his peers, friend and foe alike, will follow suit – with the intention of “winning”. The customer list of the HMCo. is fairly bristling with names like Rockefeller, Morgan, and Vanderbilt – some of these men were true yachtsmen, but for some, yachting was just another field of battle with one another.

S. Reed Anthony

S. Reed Anthony was born a proper Boston Brahmin August 5, 1863, a descendant of Myles Standish and Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor Thomas Dudley. In 1881, Reed was 18; he graduated from high school and was preparing to head off to college at Roxbury Latin School at the end of the summer, when his father died suddenly on June 12th. He would never go to college; instead he found work in December of that year at Kidder, Peabody & Company on Devonshire St. in Boston, a bank and securities company, trading in stocks and bonds. He must have found some aptitude in the vocation, because eleven years later in 1892, he founded Tucker, Anthony & Co., Bankers and Brokers with William A. Tucker, still just 29 years old. Today, he has a house on Commonwealth Ave. in Boston and a summer cottage named “Rose Ledge” in Beverly Farms. He is now 41 years old, married to Harriet P. (Weeks), with three kids – Nathan [elsewhere listed as “Andrew Weeks”], Reed Pierce, and “Miss Ruth”. Thankfully, Mr. Anthony doesn’t know that he will pass away March 10, 1914 at just 50 years of age. His obituary in The Boston Transcript on that day will include these words: “By many lines of descent he was a Puritan, but in him the granite character of his Puritan ancestors had been refined to a character of transparent quartz through which all men might read, though it’s surface none might scratch; but it was a quartz warm and glowing like that which marks Emerson’s grave in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery”.

Thetis and Wasaka

Mr. Anthony’s last yacht, which he sold last year, is a twenty-year-old cutter named Thetis. This particular vignette takes us back to N.G. Herreshoff’s first revolutionary sailboat design, built eight years before the formation of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company in 1870. Nat was 22, recently graduated from MIT, and was working as a draftsman at the Corliss Steam Engine Company in Providence – while his brother J.B. Herreshoff was building boats and steam engines under his own shingle in Bristol. The story is that NGH carved a half-model of a 37′ sloop in the pattern shop of Corliss – presumably on his own time – for J.B. to build. This would be the pattern – NGH designing evenings in Providence, and JBH building in Bristol – until they formed the HMCo in 1878. At the time, the battle in the yacht club bar was between the narrow, deep, heavily-ballasted English cutter – and the wide, shallow, centerboard American sloop. Young Nat had the idea to combine the two – moderate beam, moderate depth, internal ballast, and a centerboard. The type, naturally enough, became known as the “Compromise Type” and would be the model for Edward Burgess’ America’s Cup defenders Puritan and Mayflower. This new boat that started it all was called Shadow, and was a voluptuous shape unlike any later product of the HMCo, as well as nearly unbeatable on the racing circuit. In 1877, Shadow was bought by a new member of the Eastern Yacht Club, Dr. John Bryant. The following year, he was joined at the yacht club and

in owning Shadow by his brother Henry Bryant. Henry must have been a clever man, because just six years after getting into yachting, he decided he wanted his own boat – a sort of a big, luxurious Shadow – so, with no training or previous experience, he designed it himself. She was a compromise sloop, 64′ on the waterline (compared to 34′ for Shadow), that he had “very strongly built” by W. A. “Billy” Smith in South Boston in 1884 – and he named her Thetis. She seems to have done well – not great – racing; what W. P. Stephens called “…a very creditable amateur effort”. In 1888, Bryant designed himself a yet-bigger 90′ waterline schooner Alert, and sold Thetis. This seems to be S. Reed Anthony’s first large boat, gotten through connections when he joined the Eastern Yacht Club.

On January 8, 1904 S. Reed Anthony placed an order at Herreshoff for a new, much faster racing boat named Wasaka, HMCo #619 She was one of a pair built at the same time to a new NGH design for a 30-foot waterline racer, the other being #618 Chewink IV – about which, Forest And Stream wrote on May 28, 1904: “The Chewink IV, a 30ft. racing sloop built under new rules of measurement, was launched at the Herreshoffs’ Bristol, this week. She is a keel boat, with full, handsome stern, and slender bows, and with moderate overhangs. Considerable secrecy was observed at the shop as to her lines, as her underbody was concealed with canvas while the was building, and also when she was hauled out on the railway a day or two after launching.” Wasaka raced successfully through the 1904 season, and Anthony must have been pleased with her and his experience at HMCo., because just six months after taking delivery, he is back in the HMCo. office in Bristol to order Doris. At about the same time Doris is launched in June of 1905, S. Reed Anthony will sell Wasaka.

Late in Doris‘ first sailing season of 1905, there will be a rumor that Anthony is happy with her performance, but not her size – and he is thinking of selling her and having a larger boat built; perhaps one of Herreshoff’s large steel schooners. This made me wonder what he was used to, if the largest all-wood sailing yacht ever built by HMCo. wasn’t large enough for this 41-year old and his small family. The following is a comparison between Thetis, Wasaka, and Doris, and should stand as a warning of the risk in having a 60-ton first boat:

[table id=1 /]

Further, there is a report in the Boston Daily Globe on December 22, 1894 – before S. Reed Anthony purchased Thetis – that she had that morning been relaunched after being “remodeled” at Lawley’s City Point yard [South Boston, MA]. This was a major remodeling of the ten-year-old boat, as the article continues: “The present Thetis is some fifteen feet longer than the original one, and has a thoroughly modern forebody and bow, and a handsome stern. She will have a schooner rig, with a good sized cruising sail plan”. So, when Anthony owned her, Thetis appears to have been a schooner on the order of 87′ overall, and significantly over 60 tons.

We will never know what was said between Mr. Anthony and Nathaniel Herreshoff prior to shaking hands on Doris, much less what each was thinking. Anthony seems to have wanted a combination of Thetis and Wasaka – a comfortable cruising boat for his whole family of five and “usually an invited guest or two” (according to a contemporary yachting reporter), plus a hired crew of six – but also a yacht designed to rate well under the newly adopted Universal Rule, and put him at the top of the standings in the Yacht Club Cruises. One thing we know Nat Herreshoff has been thinking about a lot lately is sail racing rules.

Racing Rules

When you devise rules to allow dissimilar things to compete with one another, the contestants immediately begin to look for ways to gain advantage. Once one competitor finds a loophole, the others have to follow suit to stay competitive – maybe pushing the limits further still. By the time the same rules have been in place for many seasons, all the variables allowed for within the rules have been pushed to near their breaking point. To use the analogy of motorsport – S.Reed Anthony’s other sporting passion – within any racing rule, cars get more powerful and faster until accidents, usually with loss of life, cause an outcry from the public or other drivers, which leads to the rules being rewritten. Just last year, in 1903, the once-promising sport of international automobile racing was possibly ended forever, as some participants in the Paris-Madrid race reached the heady speed of 87 miles per hour on the public roads of France and Spain, and eight people were killed – including Marcel Renault, co-founder of the Renault Automobile Company. There is currently a motion in France to limit automobile speed to 25 mph, even during car races.

To race sailboats (and now as ever some people don’t seem to see the point in doing anything unless it can be turned into a competition), you either have to have a whole fleet of identical boats – like the four “New York Yacht Club 70-footers” just built by Herreshoff – or you have to agree to some sort of handicapping scheme. Now, the ancient nature of sailing vessels, and the simple grace with which they move through the wind and water belie the fact that the physics of a sailboat are incredibly complex. Here is not the place, and I am not the writer of a treatise on Naval Architecture – but if you will bear with me for a moment, a little background will help the uninitiated understand one aspect of Doris, and the contemporary boats like her.

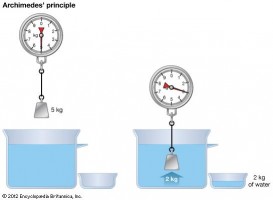

When you walk through waist-deep fluffy snow, some snow is pushed up in a lump in front of you, a trough in the snow follows along behind you, and some snow flows around your sides as the lump tries to fill in the trough. This is roughly the same as a floating displacement boat moving through the water – the Archimedes thing that you just barely don’t remember says that if your 1,000 pound boat is floating, then it is pushing 1,000 pounds of water out of the way. As that boat moves through the water, it pushes a lump of water in front of it, it is followed by a 1,000-pounds-of-water-sized trough, and water rushes around it from the lump to fill in the trough. The difference in these two analogies, though, is that when you are walking through the snowy field, your weight is still borne by your feet upon the frozen ground; the boat floats by displacing 1,000 pounds of water – regardless of the shape of that water. So, if there is a lump before and a trough behind, the boat is trying to go uphill; and the faster the boat goes, the steeper the hill. Eventually, physics places a speed limit on the displacement boat – to go any faster, because of the uphill nature of the waves it makes, the power applied must be increased exponentially. The loophole here in physics is that the longer the boat, the longer the wavelength of the lump-trough, and the faster the boat can go before it reaches it’s physics speed limit. An easier way to say that is, weight and power applied being equal, a longer boat can go faster than a shorter one. A sail-powered boat additionally derives it’s driving power from the differential of the direction and velocity of the two fluids at whose interface the boat lives – in other words, the boat is at the bottom of a layer of air, floating on the surface of the water; to sail, the wind must be moving relative to the water. The bigger the sails, the more wind it is driven by; but the boat must have enough stability to hold all that sail up. Unfortunately, if you put the 3,800 square feet of sail area from Doris onto a canoe, it wouldn’t go fast, it would unceremoniously tip over.

When you walk through waist-deep fluffy snow, some snow is pushed up in a lump in front of you, a trough in the snow follows along behind you, and some snow flows around your sides as the lump tries to fill in the trough. This is roughly the same as a floating displacement boat moving through the water – the Archimedes thing that you just barely don’t remember says that if your 1,000 pound boat is floating, then it is pushing 1,000 pounds of water out of the way. As that boat moves through the water, it pushes a lump of water in front of it, it is followed by a 1,000-pounds-of-water-sized trough, and water rushes around it from the lump to fill in the trough. The difference in these two analogies, though, is that when you are walking through the snowy field, your weight is still borne by your feet upon the frozen ground; the boat floats by displacing 1,000 pounds of water – regardless of the shape of that water. So, if there is a lump before and a trough behind, the boat is trying to go uphill; and the faster the boat goes, the steeper the hill. Eventually, physics places a speed limit on the displacement boat – to go any faster, because of the uphill nature of the waves it makes, the power applied must be increased exponentially. The loophole here in physics is that the longer the boat, the longer the wavelength of the lump-trough, and the faster the boat can go before it reaches it’s physics speed limit. An easier way to say that is, weight and power applied being equal, a longer boat can go faster than a shorter one. A sail-powered boat additionally derives it’s driving power from the differential of the direction and velocity of the two fluids at whose interface the boat lives – in other words, the boat is at the bottom of a layer of air, floating on the surface of the water; to sail, the wind must be moving relative to the water. The bigger the sails, the more wind it is driven by; but the boat must have enough stability to hold all that sail up. Unfortunately, if you put the 3,800 square feet of sail area from Doris onto a canoe, it wouldn’t go fast, it would unceremoniously tip over.

You see, then, that if you intend to race dissimilar sailboats against each other with any hope of figuring out who won, you need a mathematical formula to handicap the longer boat with bigger sails and more stability. Many types of yacht, then, for the last several hundred years demonstrate by their form exactly what was being measured to handicap them, because they always grow extreme in competition with the rules themselves:

Merchant ships have long been rated by tonnage – essentially the volume of a boat. If boats are of roughly the same type, the one with greater tonnage probably is longer, carries more sail, and has more stability to hold that sail up, proportional to that difference in tonnage, and should theoretically go faster. Up until the early 1700s, this was calculated the same for yachts as for merchant vessels – length of keel multiplied by maximum beam multiplied by depth of hold. Seems simple enough – how could this be cheated? If length is calculated by the length of keel, make the keel shorter! Make the overhang at the stern longer, and cut away the forefoot – then your boat will be longer than she appears on paper, will rate better, can carry more cargo, and will win races against more traditionally-shaped boats.

Most people seem to think that the classic English cutter – long, lean, and deep to the extreme – was just a product of British fashion of the day. Actually, the Customhouse Rules for measuring tonnage were changed sometime before 1800: rather than using keel length to calculate tonnage, they started using length on deck – so less need for short keels and long overhangs. More vertical ends give the longest waterline length for a given length on deck. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, they also started approximating the depth of hold in the volume calculations by using half the beam (which was about what the average depth was at the time). So length on deck multiplied by the beam multiplied by half the beam. That meant the beam of your boat counted against you twice, but the depth wasn’t measured at all! This began a race to build boats with infinitely narrow beam and infinitely great depth. Some of these boats are several times deeper than they are wide, and eight times as long as they are wide. There still was no effort to measure or control sail area – the natural limiting factor was the stability of the hull.

The effect of a very simple racing rule can be seen in the American sandbaggers. Overall length was limited, and that’s about it. Vertical ends are the order of the day, so that a boat 30′ overall has a waterline length of 30′ also. Sail area is absolutely massive – as much as they could hang. Stability to hold all that sail up comes from great beam, sand bag ballast that had to be shifted from side-to-side at each tack, and a gang of the biggest guys you could find – the number in the gang dependent on the strength of the wind currently; if the wind dropped-off during the race, some of the guys were asked to take a long walk off a short boat. The sparred length of these boats became about twice the length of the boat – meaning from the jib tack to the main clew – on a 30′ boat – was about 60′.

Gloriana

By the 1880s, yacht racing was a huge sport, and the rules had evolved to actually measure the speed-giving attributes of sail area and waterline length, as they understood them at the time. The Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club adopted the following rule in 1882, and it was soon adopted by most American yacht clubs. The formula is the square root of the sail added to the waterline length, divided by two, equals the racing length. More than any other, the man who showed how this logical rule could be exploited was our hero: Nathanael G. Herreshoff. The Herreshoff Manufacturing Company is now synonymous with revolutionary sailboats, but that reputation was born with hull #411 in 1891 – the great Gloriana. The hull number would suggest that HMCo had built 411 sailboats, but actually, when the first sailing vessel was entered into the Construction Record in 1883, they had already built 100 steam-powered boats; so they made the decision to start the sailing boats with #400. So, in 1891, Gloriana was only the eleventh – and by far the largest – sailboat built since the company began in 1878 (and four of those eleven were built for the Herreshoff family). She was ordered by E.D. Morgan, designed by N.G.H., and built by the HMCo. to compete in a 46-foot (waterline) class against eight other new boats by leading designers. In Gloriana, the waterline length was only 45′ 3” with an overall length of over 70′. Not only did she have long overhangs, though, for maximum length on a given resting waterline, she had very full, spoon-like ends. As important or more so than her shape, she was built very light with wooden deck and planking over steel beams and frames (what Herreshoff called “composite construction”), allowing a higher percentage of her 39 tons of displacement to be in her deep lead bulb keel. The effect was profound: in her first season, she won every race – immediately giving Nat Herreshoff and the HMCo the reputation of being the most modern American sailing yacht designer and builder, and showing all other designers and builders the direction they must go to win against the waterline/sail area rule. It should be noted, however, that while Gloriana led the way from wholesome cruising/racing yachts towards the dangerous, uncomfortable, structurally deficient all-out racing machines that would follow in the decade after her launch – she was pretty, seaworthy, long-lived, and had comfortable cruising accommodations.

This began an arms race, creating boats with ever longer overhangs, ever more sled-like hulls, ever smaller and deeper fins with bulbs of lead for ballast – not every designer nor ever manufacturer could equal the engineering of Herreshoff to build boats as light as they can be, but as strong as they must be. By 1900, many of the boats that were most competitive under the Seawanhaka waterline length and sail are rule were exaggerated scows, with no accommodations, that couldn’t sail in many conditions or make ocean passages, and were prone – through structural deficiencies – to catastrophic failure. In 1902, the New York Yacht Club decided enough was enough – they put out a call for a new rating rule to leading experts around the world. The rule they chose to adopt, and which then was so widely adopted that it became known as the Universal Rule, was written by – you guessed it – Nathanael G. Herreshoff.

The Universal Rule

![]() The simplest way to describe the change from the Seawanhaka rule to the Universal rule is to say it rewarded displacement. In the former, the waterline length was added to the sail area, and that sum was divided by a constant – so to fit in a certain racing class, the only way to get more sail area is to shorten the waterline length (and vice-versa). Under the Universal rule, the waterline length was multiplied by the sail area, and that product was divided by the displacement. Therefore, while waterline length and sail area were still played off each other the same way, now you could be allowed more waterline length, or more sail are, or even both – by having a greater displacement. The details of the Universal rule were a bit more complicated than this, and it grew more complicated over the years, as rules are wont to do, but this is the basic idea: on one side of a scale, keep the attributes that give speed to a displacement sailboat like length and sail area; but on the other side of the scale, balance those with attributes that lend wholesomeness (which is something difficult to quantify, representing seaworthiness, robust construction, and comfort), as represented by displacement or tonnage. Think of allowing a race car to have a more powerful engine – as long as it has bigger bumpers and tows a camper.

The simplest way to describe the change from the Seawanhaka rule to the Universal rule is to say it rewarded displacement. In the former, the waterline length was added to the sail area, and that sum was divided by a constant – so to fit in a certain racing class, the only way to get more sail area is to shorten the waterline length (and vice-versa). Under the Universal rule, the waterline length was multiplied by the sail area, and that product was divided by the displacement. Therefore, while waterline length and sail area were still played off each other the same way, now you could be allowed more waterline length, or more sail are, or even both – by having a greater displacement. The details of the Universal rule were a bit more complicated than this, and it grew more complicated over the years, as rules are wont to do, but this is the basic idea: on one side of a scale, keep the attributes that give speed to a displacement sailboat like length and sail area; but on the other side of the scale, balance those with attributes that lend wholesomeness (which is something difficult to quantify, representing seaworthiness, robust construction, and comfort), as represented by displacement or tonnage. Think of allowing a race car to have a more powerful engine – as long as it has bigger bumpers and tows a camper.

[A length is a simple measurement (L), but sail area is a measurement multiplied by another measurement (LxW), and displacement is a measurement multiplied by another measurement multiplied by another measurement (L xWxH) – that is why, in the formula, the length is used, multiplied by the square root of the sail area, divided by the cube root of the displacement. The resulting number is then multiplied by a constant to give a rating number]

The First Yacht of Any Consequence

L. Francis Herreshoff – son of Nat Herreshoff, and great yacht designer, writer, and historian – wrote in The Common Sense of Yacht Design “Figure 259B shows the Doris, the first yacht of any consequence built under the Universal Rule”. In An Introduction to Yachting, he similarly wrote “The first yacht of any size that I know of built under this new rule was Doris, 57′ WL which came out in 1905.” While L. Francis often seemed to delight in writing outrageous things that would have sparked a keen debate by the author’s fireside, I don’t think this was one of them – but it has become one of the controversies of Doris. In Nathanael Greene Herreshoff and William Picard Stephens – Their Last Letters 1930 – 1938, annotator John W. Streeter wrote: “ Herreshoff’s DORIS, 1905, is falsely considered the first yacht of size to have been built to the NYYC [Universal] Rule. Actually, she was constructed over the molds of Petrel, 1899. The New York Thirties of the same year were of the encouraged form and well suited to the measurement system and deserved the distinction.” So let us look critically at these contradictory statements – but imagine how much more fun it would have been to be at L. Francis’ Castle in Marblehead, with Skipper Herreshoff and John W. Streeter, before the great fireside on a raw evening, over a hot buttered rum punch, to work the matter out!

Doris was built to the same half-model as HMCo. #510 Petrel, a yawl built as a good comfortable cruiser and occasional yacht club racer in 1899 for H. Van Rensselaer Kennedy – some three years before the Universal Rule was adopted – but she was not built over the same molds. In the offset book for #510 Petrel, there is a note that Herreshoff increased all the width measurements by a factor of 17/16 (by using a scale rule that showed one foot as being 12 3/4” long), and changed the angle of the sternpost, stretching the length a little bit; new plans were drawn, a new rig designed, and new patterns and molds were needed. Below is a comparison of some statistics between Petrel and Doris:

[table id=2 /]

You can see that Doris wasn’t an exact sistership of Petrel; but even if she had been, would that mean that she wasn’t the first large yacht built under the Universal Rule? There are construction rules that govern the way a boat is built, like the Herreshoff Scantling Rules – a boat meets those rules or it does not. The Universal Rule, like all measurement rules, is just a way of measuring an existing boat – boats said to be built to a rule simply rate favorably under that rule. She may have come from an earlier model, but did rate well under the new rule – and this is no accident. The Universal Rule was conceived, written, and adopted for the reason of allowing good boats to rate better than they had under the waterline length/sail area rule. While he wrote the rule in 1902, there is evidence that Nat Herreshoff was thinking about a new measurement rule that would encourage displacement by 1891 when he was revolutionizing bulb and fin keel yachts. By 1899, he had been thinking about this for about a decade, and when a potential customer, H. Van Rensselaer Kennedy, asked for a boat that would push the limits of the Seawanhaka Rule, but for a boat that would be a good boat, that is just what NGH modeled for him. And it turned out to be a very good boat indeed. Six years later, when S. Reed Anthony asked for a similar boat, Capt. Nat probably looked back on his recent designs with an eye to how they would rate under the new rule – rated well – and a small increase in displacement would allow an increase in sail area without changing the rating – and was born. I don’t believe Nat Herreshoff wrote a rule to favor good boats and then immediately began designing boats to fit that rule; I think he knew what a good boat was, he had built them when he could, and he succeeded in getting a rule adopted that didn’t penalize good boats.

That the New York 30s were the first fleet of one-design boats designed specifically for the Universal Rule, I fully agree. Even L. Francis says as much in the next paragraph after Doris. And even though they were introduced the same year as Doris, and the first NY 30, Alera, was HMCo. #626 (the next contract signed after Doris, five days later), Alera was launched January 3, 1905 – more than four months before Doris – and only 17 days after NGH wrote the above notes in the offset book for Petrel, which began the design stage of Doris. But even though L. Francis Herreshoff designed the H-28 to fortify your soul against a world of warlords, politicians, and fakers – he phrased his comments on Doris just like a politician: calling her “the first yacht of any consequence” and “the first yacht of any size” to be built under the Universal Rule. No one can say that this is wrong – because “of any consequence” might mean, to him, a yacht built by the HMCo.; “of any size” might mean over 50′ on the waterline. It is as subjective as if he had said that Doris was the first yacht painted the correct shade of white built under the Universal Rule – you may not agree, but he is not wrong.